The Wager

It was just after the lunch hour. The poorly ventilated auditorium of the law faculty was dark and stuffy, as usual. The creaking ceiling fans were doing little more than to circulate the warm air, as usual. The final year class was paying rapt attention to Professor Okeke, as usual. And then quite unexpectedly the unusual happened.

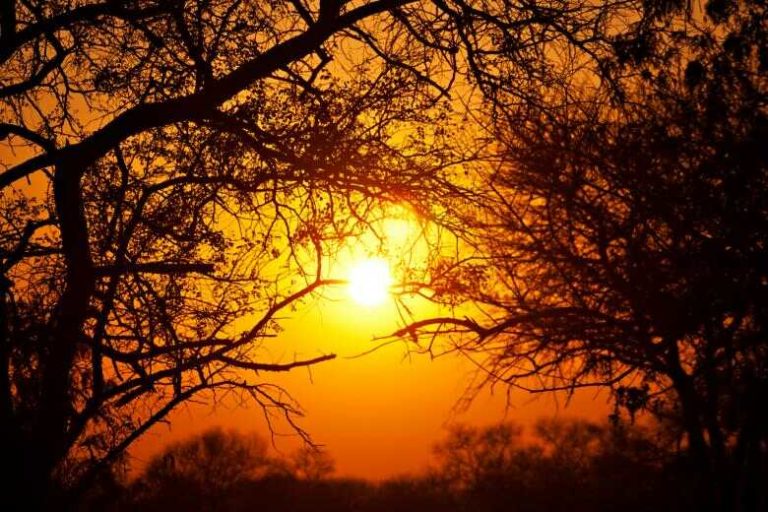

A hum arose, the class turning from Prof towards the door. There, framed against the doorway by the blazing sun, was the statuesque figure of Yvonne Oki. One slender arm cradled books against her bosom and the other gripped the strap of the trendy bag slung over her shoulder. She peered into the auditorium before deliberately reaching inside the bag to deliberately bring out her phone which she deliberately switched off. A chill swept through her seated classmates despite the weather. The most beautiful girl in the law faculty could not have suddenly taken leave of her senses, could she? Surely she could not be planning to walk into Prof’s class mid-lecture, could she?

Professor Okeke taught jurisprudence, a compulsory course which had to be passed for the bachelor’s degree. It was already difficult enough, an “abstract” course the students called it, filled with obscurant musings about law by mostly white men who were mostly long dead. It did not matter to the students that one of the most notable of those men, Thomas Aquinas, was African – he was as bad as the rest with all his difficult philosophizing about whether law was “natural” or not.

The students would have hated jurisprudence whoever taught it but Professor Okeke had elevated the experience to a form of torture. It was common knowledge that he initially trained to be a Catholic priest in France. The truncated stint at the seminary bestowed him with fluency in not only French but also Latin. He would conjugate jurisprudence’s big words in the one language and then in the other before asking the random student to explain the relevant terms, albeit in English.

The staccato questioning would start about halfway through the lecture and continue for the rest of it. Petrified students squirmed in their seats as this modern-day Torquemada trudged up and down the aisles, each hoping not to be the next unfortunate fixed with his bespectacled glare and then the dreaded, “you sir, would you explain …” It was always “sir” whatever the gender of the student, for as all knew, Prof considered that there were no women at the Bar.

“Have ever seen him ask me a question?” Yvonne asked George. Yvonne and George were cousins and hung out regularly on campus. This night they were seated at “Base,” a bush bar behind the women’s hall of residence. George was lamenting how Prof had destroyed him earlier that day with some unfathomable question about Plato.

“What do I care about Plato? The man has been dead for over a million years, I beg.”

Yvonne laughed. “But Georgie,” she said, placing the emphasis on the second syllable so it came out as “jhor-JHEE,” “you should have seen yourself. We think say you want shit for trouser.”

“I beg, leave me hand,” George retorted, matching her switch to Pidgin English. “We dey wait; one day it will be your turn.”

“But that’s what I’m trying tell you now,” exclaimed Yvonne, “it won’t happen!”

“And why do you say so?” George asked. “That Prof is no respecter of persons, I swear. He seems to enjoy picking on the hot babes especially.”

With a twinkle in her eye, Yvonne affirmed, “I’m telling you it just won’t happen; not to this babe at least.”

She raised her hands above her head and shook herself from side to side, laughing excitedly, like one celebrating a victory.

George took a swig of his beer and spluttered, “You girls can like to deceive yourselves. Don’t worry, that day will come. Just remind me not to laugh too much at you.”

Yvonne’s laughter receded. She seemed to mull over what she was going to say next. Then she leaned over and crooked an arm around George’s neck.

“Let me tell you something, my dear bro,” she said, almost whispering. “That Professor whom all of you are so afraid of is dying – I say d-y-i-n-g – for little me. He’s been hitting on me o, left, right and center, from day one of Jurisprudence.”

She waited a moment for her words to sink in and then started to laugh again, rocking from side to side, with her hand still around his neck.

“Impossible,” exclaimed George, extricating himself from her grip and turning his head to regard her with a look of disbelief. “Prof? Prof? Which Prof? I beg, pull the other leg. We’re not even sure that that one likes women. Have you seen the way he dresses?”

Professor Okeke was always well groomed, coiffed and attired. The contrast between him and the rest of the faculty could not be starker. Where other law teachers seemed bent on living up to the stereotype of the shabbily dressed, absent-minded professor, Prof was the epitome of sartorial. To all who beheld him, there could be little doubt that he had a line to Mai Atafo, the menswear stylist.

Prof foreswore the black suits that were de rigueur in the law faculty. “Noir est port les morts,” he had been heard to say, denouncing that most somber of colors as only fitting for the deceased. He turned out instead in hues he deemed tropically appropriate (“tropicis signis”): light blues and greys, usually in cotton or linen but rarely wool. Whatever the preferred (but never black) shade for the day, the suit would be beautifully tailored and set off by pristine, cotton shirts and luxuriant ties. Cufflinks, tie pins and pocket squares accessorized the haute couture ensemble.

If Prof’s lectures were on a Friday, he dressed down. The suits were replaced by unconstructed jackets and chinos. Soft leather loafers supplanted the spit-polished Oxfords that were weekday staples. A cravat completed the business casual look for as all knew, Prof’s neck could not be unshorn.

The dapper academic’s attention to detail did not stop at apparel. Prof’s face had the sheen of a man who availed himself of the moisturizers, cleansers and other facial care products that had inveigled their way into men’s bathroom cabinets. Despite the heat, he never seemed to sweat. His full head of hair, tending towards an afro, was always trimmed and lined around the temple and at the back of his neck. He parted it left of center, in the fetching manner of Patrice Lumumba, the Congolese nationalist.

Yvonne laughed at George’s wide-eyed disbelief.

“Look here, brother me, let me show you something, doubting Georgie like you.”

She thrust her phone into George’s hands and showed him texts from a contact named “Mugu 4.” They were all soppy, lovelorn messages. There was a smattering of French and Latin phrases in many of them. One seemed to be a poem in Latin. Another reproduced lyrics from the Afrobeat song, “African Queen.”

It was George’s turn to laugh. He was particularly tickled by the sobriquet Yvonne had assigned to the sender of the messages. “Mugu,” someone prone to deception, the moniker much beloved of 419 scammers.

“How many mugus exactly do you have on this phone? And wait; am I also mugu-something?”

George chortled as he made to access her contacts list.

Yvonne snatched her phone back, laughing.

“Come on, give me my phone!”

“But that proves nothing-o,” George asserted, drinking more beer. “The mugu fit be anybody, even one of our classmates trying to denge pose like Prof.”

Yvonne shrugged, “Prove what? I’ve told you-o; if you don’t believe me, that’s your business.”

George set down his bottle. He leaned forward, resting his elbows on his laps and interlocking his fingers.

“Ivonime, Ivonime, Ivonime. How many times have I called you? I beg, fashi; Professor Okeke does not chase women talk less of a student like you, as fine as you be. You hear me? He does not chase women.”

Yvonne’s name was really Ivonime. Like all “woke” babes on campus, she had anglicized it. You could not be woke and have some “bush,” native name, like some mgbeke from the village.

Yvonne, a certified, thoroughly woke babe, now felt challenged.

“You’ve called me three times, Georgie and it is three times too many. Look, seriously, do you want to bet on this thing?”

Thus it came to be that Yvonne was standing conspicuously outside the auditorium well after Prof’s class had started on this hot afternoon. It had not needed any stretch of the imagination to arrive at an appropriate wager between the cousins. Professor Okeke was a punctilious timekeeper. He started his classes on the dot of the hour and finished similarly. He did not tolerate lateness.

In one oft-recounted incident, a class preceding Prof’s had overrun in another lecture hall. The students emerging from that class arrived at the auditorium to find that Prof was already ten minutes into his lecture. He broke off only long enough to give the gaggle congregating at the door a stern warning not to attempt ingress. The incredulous students were therefore forced to stand outside taking notes as best they could as Prof finished an hour’s lecture to a vacant auditorium. He even walked the empty aisles from the half-hour mark although it was the only time anyone could remember that the dreaded “And you sir …” was not part of the exercise.

Now, with all eyes fixed on her, Yvonne dramatically stepped into the auditorium. Her pace was measured, heels clicking and clacking in the pin-drop silence as her peers watched with trepidation. Prof had stopped teaching. Yvonne was now in the firing line. Surely, an explosion was coming. Or was it?

Yvonne got to the front of the lectern and paused, her back to the professor. She surveyed the ascending rows for an empty seat. She seemed oblivious to the immaculately attired figure behind her who stood wordless at the lectern, his designer glasses glinting and an odd, strangulated look on his face.

After a seeming eternity, Yvonne espied a spot at the top of the auditorium and began to make her way up slowly. She had chosen a seat in the middle of an occupied row. Students had to get up, moving bags, laptops and notepads to let her through. The seat bottoms swished up, thudding against backrests as the row progressively rose for Yvonne. It was a commotion most unbecoming of the jurisprudence hour. Yet, Prof stood, transfixed, saying nothing and doing nothing.

Eventually, Yvonne got to her preferred seat. She made another deliberate show, of bringing out her books and gathering her weave at the back of her head with a band. The students cast astonished if furtive glances from Prof to Yvonne. Still nothing happened. There was no explosion, no multilingual rant, nothing – not a word from Prof. She sat, silence reigning once more, with notebook open, pen poised in hand.

And then, like one emerging abruptly from a trance, Prof resumed his lecture.

“As we shall see, critical legal studies were preceded by the realist school whose main proponent

was Oliver Wendell Holmes …”

The students were jolted back to their note taking. That day, for the first time in living memory, Professor Okeke did not venture up the aisles. He did not ask anybody any questions. He did not speak any French or Latin. He also finished his lecture a full ten minutes before time and was sweating profusely by the end.

After Professor Okeke departed, uncharacteristically mopping his brow, if with a monogrammed handkerchief, it was an animated final-year law class that spilled out of the Amphitheatre. They were full of excited chatter, trying to comprehend what had just happened. All bar two. That night, George handed over one thousand Naira to Yvonne. She graciously used some of it to buy him beer.